Literary Cultures in Small Towns

“Small towns boast of a flourishing literary culture around tea stalls, in mushairas, kavi samellans and through widely available literature in vernacular languages. Get a peek into the intriguingly colorful literary cultures in small towns.“

Truth is often stranger than fiction, and yet it is often in stereotypes, far removed from truth, that we put our trust in. Case in point, literary culture is highbrow; it caters only to high fashion and taste, and only found in the metros and cities.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The prevalence of this myth is just another proof of myopia of perception from which most of the makers and consumers of culture suffer from. The colonial hangover, which makes them enthralled with English, as the only sign of good taste, has yet not faded away in many cases.

Literature and literary cultures thrive as much in small towns as in the sprawling metros. They differ in the language, distribution and reception; difference and in-existence are synonyms in no dictionary. Anyone casting aspersions on the claim must educate themselves on the prolific tradition of literary culture that transacts in vernaculars, also found thriving in small town India and villages.

What is literary culture?

However, we must begin at the beginning: What is the definition of literary culture? Literature essentially means a body of writing that attempts to look at the human condition and world in a new light. Sherlock Holmes quipped: ‘There is nothing new under the sun Watson, it has all been done before.’ Equally, there is nothing new to be said, it has all been said before. Literature, to take refuge in a simplification, is simply telling all what has been said with a slant, to borrow a line from Emily Dickinson. Good literature, often held synonymous with literature, presents the world in a light that appeals more.

Onwards to Culture. Very simply said, culture is an amalgamation of practices – food, dress, language, rituals, architecture, religion – the experience of lived life, in short.

Combine the two and you have literary culture. It implies not only how a work or body of literature is produced, read, experienced and distributed, but also how literature depicts food, dress, language, rituals, architecture, religion – the experience of lived life, in short. It is not restricted just to formal literary magazines, but is shaped and in turn shapes authors, readers, bystanders, hawkers, and publishers, book sellers. It comprises books, journals, newspapers, pamphlets, songs, recitals, stories; everything that deals with human experience. Nothing is sacrosanct, and nothing that can’t find a place in this admixture of culture.

Literatures of vernacular

Salman Rushdie infamously claimed in a 1997 New Yorker article that India hasn’t produced any significant writing in vernacular languages after independence. ‘Blind as a beetle’ couldn’t find a more fitting context. Literature in vernaculars is widely produced and distributed in today’s age

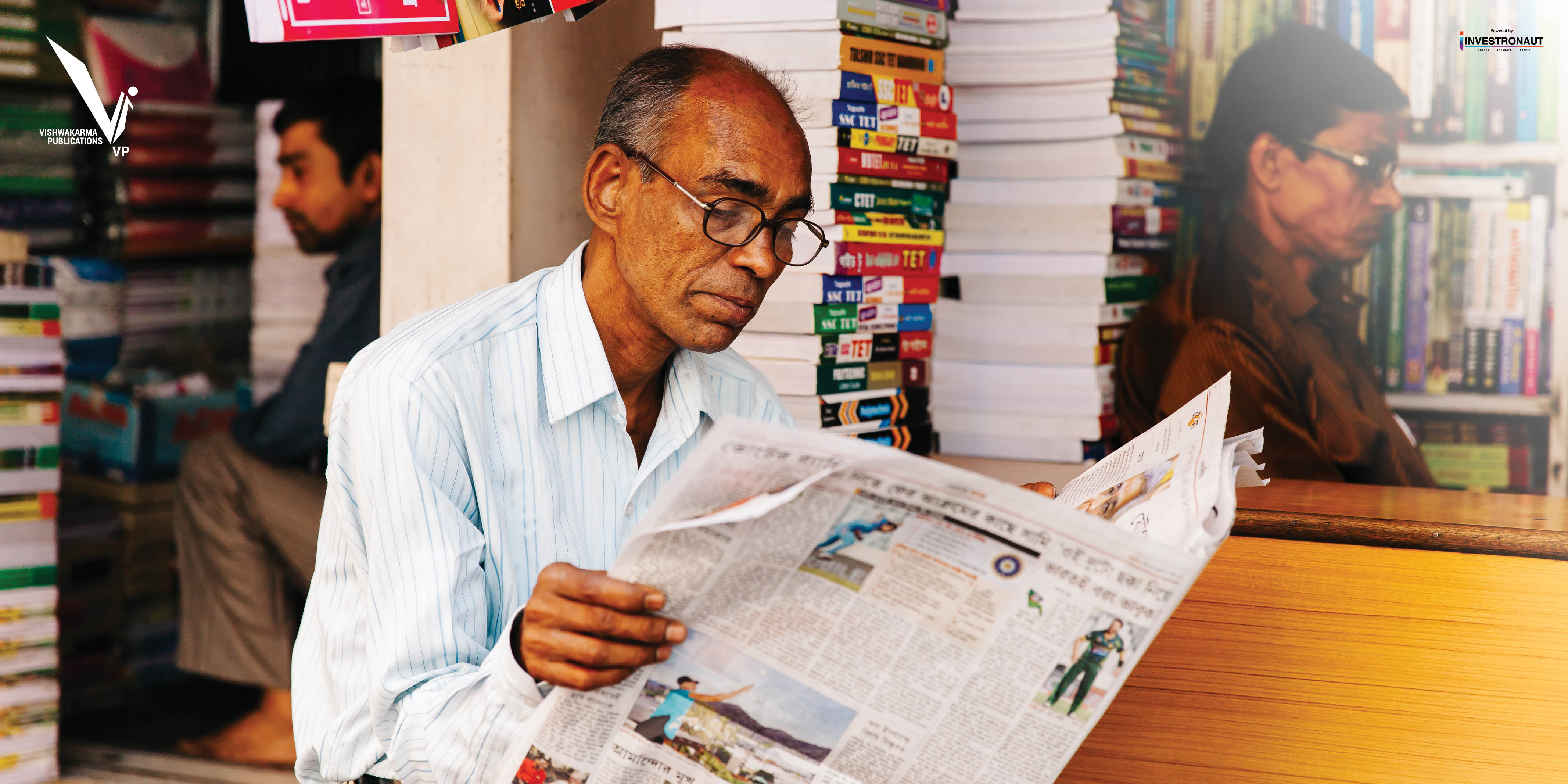

My mother is a voracious reader though she can’t spell voracious let alone know what it means or what category of speech it belongs to. She devours everything she can lay her hands on in Hindi – magazines, comics, even torn flyers and the old newspapers wrapped around the ironed clothes by the dry cleaner. Growing up in my village in North India, access to literature in Hindi was never a problem if you were willing to travel to a bookstore in a nearby city. The challenge was to find English books. When I visited the only bookstore in Meerut that stocked literary books in English, I had little choice in terms of genre, or writers as the shop mainly stacked books in Hindi. Books in English had to be ordered on demand from Delhi. One of the founding principles of economics is: If there is demand, there is supply. Surely, it wasn’t ghosts who demanded the books in Hindi.

Informal spaces of literature

Unlike in metros and cities, small towns don’t have designated reading spaces like huge libraries or cafes. Rather, the tea stall, a roadside shade, a park, courtyards or houses of people serve as places of exchange of ideas. In an intriguing feature for Indian Express titled ‘Tea, Time and Kashi’, Dipti Nagpaul walked alongside the renowned ‘Hindi writer Kashinath Singh through Assi Ghat’. The walk illumined her to Varanasi’s tea stalls and pan stalls which doubled as addas for poets, writers and artistes. These tea stalls are the chief centers of democratic public debates on politics and literature. As Ghalib said: I too possess a language/if only you’d ask. What do they know of thriving small towns, who only dead mega cities know?

Alternatives of literary festivals

Small towns have their own versions of literary festivals in vernaculars in the form of ‘Kavi Samelan’ and ‘Mushaira’. Some of them held in Banaras, Meerut and Lucknow are amongst the oldest and most prestigious. These congregations of writers and poets are at their satirical best, no holds barred assemblies, where not even the Prime Minister of the country and gods are exempt from ridicule.

Fewer literary trends

It can be argued with some trepidation though that since access to technology in small towns and the outer world is less, at a given point of time only English literature of a particular brand is followed. For example the advent of popular literature like Chetan Bhagat or Ravinder Singh which is easily understood, has found a huge market equally in smaller towns where word of mouth publicity is greater. Diversity in trends is more in cities.

Due to diminished visibility of books in vernacular, and lack of networks in the smaller towns, they may have a hard time translating their creative resources into economic outcomes over the metros. That lack of monetization or hype, however, certainly doesn’t mean that culture and creativity is only an urban phenomenon. The English might have left, but they left their biases behind!

The author of this article, Richa Singh is a content writer with Investronaut.